Blog Short #192: No One’s Going to Save You

Photo by Frazao Studio Latino, Courtesy of iStockPhoto

That’s a rather sobering title, isn’t it? But it’s true. Whether you’re doing your best or not doing your best, you are responsible for how your life proceeds. No one else can do it for you.

That doesn’t mean that things don’t happen beyond your control. They do and always will. It means that you have choices about how to react to what happens. You also have choices about what you initiate and pursue and how you conduct yourself throughout your experiences.

Here’s how I learned this lesson!

I learned all this the hard way, and unfortunately, many of us seem to learn that way.

At one point, I got into horrible credit card debt. I won’t tell you how much because it’s embarrassing.

It happened when I partnered with someone to open and run a business. We went into it with pie-in-the-sky expectations, lots of enthusiasm, and confidence that everything would go well. If you’ve ever been an entrepreneur, you know this mindset.

Sure enough, it wasn’t long before we maxed out our credit cards to make ends meet because we hadn’t done our research ahead or prepared for any obstacles.

After lots of blaming this and that for the failure – the economy had turned on us, our location was wrong, we didn’t have the right staff, etc. – we had to come to terms with the debt.

I kept hoping for some miraculous help or magic windfall to set things right, but that rarely happens in real life. Eventually, I had to admit that we hadn’t been smart, and the fault was ours.

We made a plan to pay the money back over three years, which involved working more and tightening up spending. It was grueling, but in three years, the credit cards were empty.

Here’s what I took away from that experience that has stayed with me and might come in handy for you, too, if the situation arises.

1. No one is going to save you. You must take responsibility.

The first step in saving yourself is to accept and acknowledge what you’ve done or not done that’s resulted in your current situation.

It’s not the economy, global warming, the government, your friends, or your family. It’s you. Once you accept that, you can start your trek back up.

When I realized I would have to work a lot more over a long period of time to pay back all that money, I wasn’t happy. Yet, once I accepted the situation and started working on it, I felt some relief.

When all the money was paid back and my credit score zoomed up, I was grateful that no one had saved me and that I had to learn the lessons involved. I wouldn’t have it any other way because those lessons have stayed with me, and life is better as a result.

2. Practice self-sufficiency.

You might be on top of certain aspects of your life but irresponsible with other parts of it.

Maybe you’re a super salesperson and bring consistent money into the company, yet show up late for meetings, forget to pay your bills on time, let your laundry pile up, and neglect your dog.

It’s essential to take care of yourself and your responsibilities across all areas of your life, and be aware of how your behavior affects those who rely on you.

When you neglect responsibilities, you will eventually sabotage yourself, and the consequences will seep into your successes and disrupt them.

Again, no one can save you. Even if someone steps in to help, until you recognize and correct your dysfunctional behavior, the patterns will repeat. And people will know they can’t count on you.

3. Think ahead.

Much of the pain people encounter could have been prevented if they’d thought ahead.

That’s nothing new—I’m sure you’ve heard that many times. But have you taken it in and applied it? It’s not easy to do so because emotions get in the way.

Emotions are essential and provide interest, drive, and energy, but they need to be tempered by thought, objectivity, and evaluation.

When you decide on a course of action, consider all the things that can go wrong. That doesn’t mean being a pessimist – it means being aware of what you might encounter as you take action.

I’m an optimist at heart, and optimism is energizing when you have a goal, but make sure it’s grounded in reality so that you take the necessary steps to be successful in your endeavors instead of going full-speed onto the expressway with only half a gallon of gas in your tank.

4. Stop blaming!

When things go wrong, it’s easy to start a litany of blame.

Sometimes, you blame other people, surrounding circumstances, and unforeseen changes. Other times, you blame yourself, but not in a constructive way. You shred yourself and keep doing it until you’re immobilized. In truth, extensive self-battering is another form of avoidance.

This is called the shame-blame circle, and it’s like stepping into a whirling eddy and drowning. The better approach is not to blame but to look at the actions and factors that led to the situation and review what you could have done differently to get better results.

How can you avoid making the same mistake again, and what can you do now to correct the situation?

It’s not about who’s to blame, but what you can learn.

5. Look for patterns.

One of the facts of life is that you will encounter the same obstacles repeatedly until you resolve them.

In other words, the same crappy situations come at you until you face them.

Worse, they get stronger and louder if you don’t pay attention.

So, if you drink and drive, you might run over a curb while parking and get a flat tire. If you drink and drive again, you might get a DUI and lose your license for a while. If you do it again, you might have an accident where someone is hurt.

That’s an obvious example, but some situations are more subtle and require greater self-awareness and honest evaluation. For instance, many minor infractions at a job can pile up until one day, the boss calls you into her office and fires you.

Get good at observing yourself in all your interactions and behaviors to make sure that you aren’t:

- Repeating the same mistakes over and over.

- Avoiding awareness of what you’re doing and the consequences of your actions.

You want to stay on top of your own personal trends. “Trends” is a good concept here because it puts single actions and behaviors within the context of how your life is moving.

You rarely stand still. You’re either going forward or backward, and it’s in your best interest to know which way that is. If you don’t, you give up your control, yet you’re still responsible for how it goes.

You wouldn’t go out into the ocean on a speed boat and sit in the back while the boat sped willy-nilly across the water. Even if the boat is idling, it’s still moving. Grab the steering wheel and take charge of the direction and speed so you go where you want to go.

That’s all for today.

Have a great week!

All my best,

Barbara

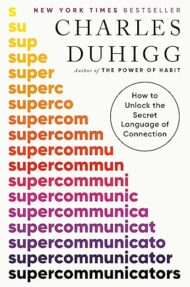

First up is Charles Duhigg’s Supercommunicators, a super-read and one of the most comprehensive books on communication I’ve encountered.

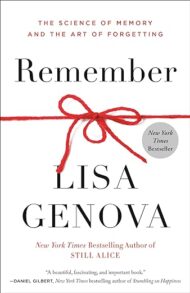

First up is Charles Duhigg’s Supercommunicators, a super-read and one of the most comprehensive books on communication I’ve encountered. Remember by Lisa Genova is an all-in-one treatise on how memory works, how to improve and protect it, and when and why it’s faulty.

Remember by Lisa Genova is an all-in-one treatise on how memory works, how to improve and protect it, and when and why it’s faulty. Rapport is our second book on communication. The authors are both well-known forensic psychologists who participated in developing a “model of rapport” based on over 2,000 law enforcement interviews. Their book is the result of this endeavor and lays out their model.

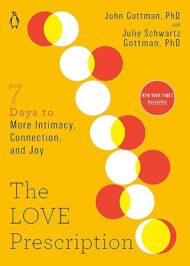

Rapport is our second book on communication. The authors are both well-known forensic psychologists who participated in developing a “model of rapport” based on over 2,000 law enforcement interviews. Their book is the result of this endeavor and lays out their model. The Love Prescription is the newest book by husband-and-wife team John Gottman, Ph.D., and Julie Gottman, Ph.D. The title is apt because it outlines a roadmap to improving your marriage (or intimate relationship) with concrete, specific actions based on proven research.

The Love Prescription is the newest book by husband-and-wife team John Gottman, Ph.D., and Julie Gottman, Ph.D. The title is apt because it outlines a roadmap to improving your marriage (or intimate relationship) with concrete, specific actions based on proven research. I’ll start with an opening statement that pulls you right into the message of this book. The author says:

I’ll start with an opening statement that pulls you right into the message of this book. The author says: We live in a culture that promotes optimism and positive thinking, both of which have proven results. However, negative emotions are necessary and have value.

We live in a culture that promotes optimism and positive thinking, both of which have proven results. However, negative emotions are necessary and have value.