Blog Short #242: How to Build Trust in Your Relationships (6 Practices)

Photo by Alistair MacRobert on Unsplash

If people trust you, everything is easier. You get better jobs, your intimate relationships are stronger, your kids feel cared for, and friends value your friendship.

Even if you already think that you’re trustworthy, it’s a good idea to take a quick assessment of the following habits and practices and measure your behavior against them.

No one’s perfect, and most of us have areas that still need improvement. Having the list will help you figure out where you need to make some changes.

This article is a companion piece to a previous article titled “9 Characteristics of Trustworthy People.“ That article provides an overview, but in this article, we’ll delve more specifically into behaviors.

1. Keep confidentiality.

You might say, “Of course!” But it’s not that easy, especially in families or among close friends. We all talk about each other. It’s normal.

However, the people you’re closest to want to know that they can tell you something and you’ll keep it to yourself, even if they haven’t specified it. You intuitively know it would upset them if you were to disclose it, so you don’t.

You understand how they would feel if you were to discuss their secrets with others. Embarrassed, exposed, weakened in others’ eyes, or having to explain themselves to people who don’t need to know.

No matter your intention, it’s a betrayal, and once done, it puts a dent in the trust between you.

If you believe the issue needs to be addressed with others, then state that upfront. Don’t promise to keep confidentiality and then decide later that you can’t uphold that promise.

If you’re not sure going in, make that clear also. Strive to agree on who needs to know if that applies.

2. Don’t use personal information someone has divulged to you against them later.

This is a big one with lots of emotional fallout.

When someone shares something about themselves that they see as a weakness or vulnerability, they want to know you won’t use it against them later. This is especially true with couples and family members.

For example, my husband and I are both psychotherapists, so you can imagine the things we’ve shared about our backgrounds and psychological issues we’ve each had to address. Consequently, we’re very careful not to use that knowledge against each other when having disagreements. Doing so would be damaging.

You must keep personal disclosures separate from disagreements or arguments and avoid saying something in anger that touches a sensitive subject or emotional sore spot.

If you don’t, your partner (or whoever) will start closing up and not trust you with vulnerable information.

Using someone’s vulnerability against them is a betrayal and erodes trust.

The closer and more vulnerable you become with someone, the more trust becomes a focus.

3. Follow through.

Whatever you promise to do, do it! And if you can’t, let the other person know as soon as possible.

Your reason should make sense, and you should have a plan to make good on it.

The closer you get to someone, the easier it is to take them for granted. If you tend to run late, and they know that about you, what’s the big deal? You’ll get there eventually, and they know you will.

The big deal is that it shows a lack of respect and care for their time.

If you don’t follow through on things, you show a lack of consideration and care for the other person’s feelings, along with a lack of respect.

You may not mean any of that, but taking advantage of someone’s understanding and patience with you has consequences. If done a lot, resentment builds, even if not verbalized, and seeps into trust.

Some people have no trouble being on time, showing up, and following through; however, others struggle with these issues, especially those who are genuinely ADHD. I’ll discuss this next week.

For now, if you or someone you care about faces this challenge, it’s important to discuss it and develop strategies before it affects your relationship and trust.

4. Don’t keep secrets.

Secrets in relationships have a way of surfacing sooner or later, and, in most cases, aren’t well received.

If you’re keeping secrets from your partner, older kids, or friends, examine your reasons. Ask yourself:

- What am I afraid of?

- What will happen if I’m found out?

- What are my reasons (other than fear)?

It’s normal not to say everything you’re thinking and feeling. However, when building a close relationship based on trust, you should be able to express your thoughts and feelings as long as you’re respectful.

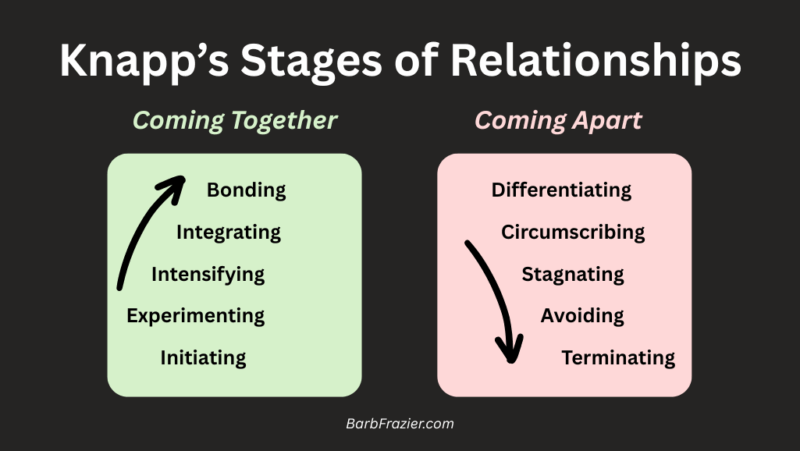

Closeness and self-disclosure go together. The closer you are, the more you reveal the intimate details of who you are, what you value, your struggles, and your aspirations.

Keeping secrets can feel dishonest and undermine trust. Plus, it’s stressful to hide things from someone you care about because there’s the fear that you’ll be discovered, and then what?

If you’re in a committed relationship and want to build trust, be open and honest, and don’t keep things from your partner. That’s assuming, of course, that you can trust them too.

5. Be there.

There are many ways to be there for someone. Any of these apply.

- Be emotionally available and accessible. Share your feelings openly and encourage the same for the other person.

- Show interest and concern by talking, touching, checking in regularly, and paying close attention.

- When spending time together, be present. Pay attention to the other person unless you’ve both agreed to do your own thing while together. That can be comfortable too, if agreed upon.

- Spend enough physical time together to satisfy each other’s needs. This applies to couples, family members, friends, and especially parents and their children.

Knowing that someone wants to be with you and is concerned about what you need is a significant part of trust.

6. Avoid lying.

Lying is implied in all of the above factors but deserves a category of its own.

Lying erodes trust faster than anything else. Even little white lies told to avoid arguments have an adverse effect.

You might put off discussing something for a better time, but lying outright will almost always backfire.

You want to feel secure that what your partner, friend, or family member is telling you is true. And you’d prefer not to have to question that. This applies to your boss or work colleagues as well.

Children will naturally lie to you sometimes out of fear or to see how far they can go. However, you still teach them that lying is wrong and damages your trust in them. It also goes both ways: lying to your children erodes their trust in you as well.

Practice telling the truth if you tend to fudge things or tell white lies. If you grew up with abusive parents, you might have learned to lie to stay safe, and that makes sense. But as an adult, it’s not a healthy habit.

Two Key Guiding Principles

The key guiding principle to building and maintaining trust in any relationship is to gauge how your behavior will affect the well-being and feelings of the other person. In other words, empathy.

A second focus is contact. By that, I mean emotional contact and physical presence. Both are necessary for building trust, as well as for intimacy and closeness.

Nothing takes the place of being in each other’s presence while emotionally available.

Strive for both and follow the guidelines above, and you’ll build trust, commitment, and growing affection simultaneously.

That’s all for today.

Have a great week!

All my best,

Barbara