Blog Short #224: Why Anxiety is Worse in the Mornings and How to Shake It

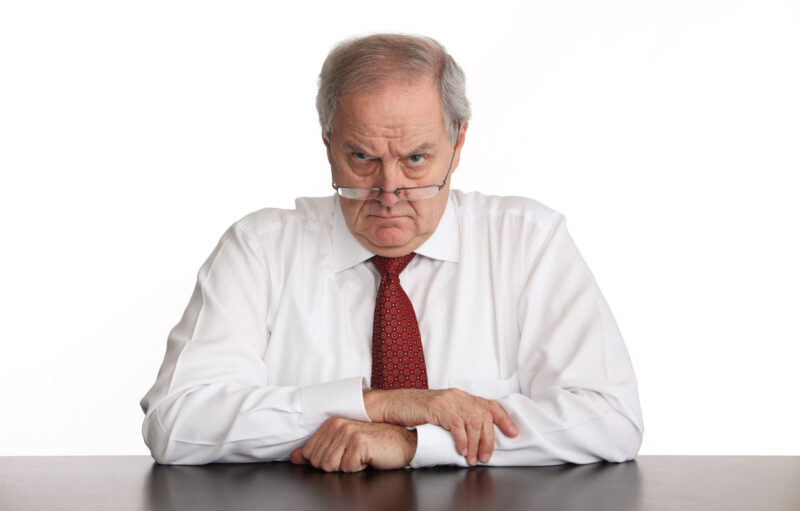

Photo by fizkes, Courtesy of iStock Photo

Does this sound familiar to you?

When I wake up some mornings, I feel like my heart’s going to pop out of my chest, my mind’s running a marathon, and all I want to do is pull the covers over my head and pretend I don’t have to get up.

If you’ve ever had that experience, you know what morning anxiety feels like.

But why? Why do people feel more anxious in the morning than later?

You would think you’d feel rested and less anxious since you’ve been asleep for hours. But not so.

Today, I’ll explain why we have morning anxiety, what it feels like, and what you can do to minimize it.

What it Feels Like

The symptoms are both physical and psychological. Here’s a quick list.

Rapid heartbeat. Anxiety increases the release of adrenaline, which causes your heart to beat faster. You might have palpitations and hear your heartbeat pulsing in your ears. Some people complain of tightness in their chest or an aching.

Difficulty breathing. You can’t get a full breath. You either hold your breath or breathe more rapidly and shallowly, causing hyperventilation. The more you notice it, the worse it gets. You might feel dizzy or light-headed.

Sweating or shakiness. Some people tremble or feel shaky.

Gastrointestinal problems. When you’re in fight-or-flight mode, your body shuts down systems that aren’t necessary to fend off the current threat.

Your digestive system is the first to be affected, resulting in gastrointestinal symptoms such as acid reflux, diarrhea, constipation, and stomach pain.

Racing thoughts and overthinking. Anxiety activates your emotional brain while setting up a blockade for your thinking brain. You fixate on worst-case scenarios, repetitive worries, and catastrophic thoughts about the day ahead. You feel overloaded and struggle to regain control of your mind long enough to calm down and think clearly.

Difficulty concentrating. Your attention span diminishes, and your ability to focus is hampered. You may experience brain fog or overload and have trouble making decisions or taking action.

Avoidance. Anxiety can be paralyzing. You find yourself procrastinating and wanting to stay in bed. You might pick up your phone and start scrolling mindlessly to numb yourself.

Sense of foreboding or dread. Some people describe feeling like something terrible is going to happen even though there’s no evidence to back it up. You feel negative with heightened awareness.

Irritability and anger. Anxiety is uncomfortable and leaves you feeling irritable, unable to relax, snappy, fidgety, and easily triggered.

What Causes It

Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR)

Cortisol levels (the stress hormone) increase as you wake up in the morning for 30 to 45 minutes.

The intensity may be heightened if you’re already feeling anxious about something or have health issues. For instance, if you go to bed obsessing about a problem, you might feel even more anxiety than usual in the morning.

Cortisol naturally alerts your amygdala (the emotional brain) to potential threats, which can elevate your anxiety and lead you to conjure up worst-case scenarios. It can also increase your heart rate, tense your muscles, and make you jittery.

Your Brain’s Default Mode Network (DMN)

When you’re not actively focused on something, your brain goes into default mode. It sifts through memories, past experiences, self-reflection, and thoughts about the future. Your mind wanders.

If you’re already stressed or worried, your DMN will lean towards the negative and fear-based mind scenarios that increase your anxiety.

You’re in a passive state when you wake up in the morning. You’re vulnerable and open to the mechanisms of your DMN. Subconscious material is more apt to surface and intrude on your conscious thoughts. When you add more cortisol to the mix, you experience a potent dose of anxiety.

The enemy sneaks up on you before you’ve had a chance to arm yourself for defense.

Unresolved Issues and Stress

You finished the day with problems hanging in the balance you couldn’t resolve. You might have dreamt about them with no solutions.

As soon as you wake up, the problems resurface in your mind, and you feel that anxiety all over again.

Poor Sleep

The sleep issue is a catch-22 because you need good, solid sleep to help you stay calmer and able to think clearly, yet stress and anxiety prevent you from sleeping well.

To make matters worse, if you enjoy a few drinks in the evening or consume large amounts of comfort food to soothe yourself, your sleep quality will suffer. You’re likely to wake up during the night and struggle to fall back asleep or toss and turn for most of the night.

You’ll be less able to handle your anxiety when you wake up.

Anticipatory Anxiety

We’ve already mentioned unresolved issues, and anticipatory anxiety is part of that process. You have a problem that looms over you, and upon waking, you start overthinking it.

You anticipate the many potential negative outcomes, which all skyrocket your anxiety and leave you precariously dangling on an emotional cliff.

Generalized Anxiety

Situational stress can lead to acute anxiety, but it fades once you resolve the situation. Some people have Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), which results in frequent anxiety, often without an obvious trigger.

If you struggle with generalized anxiety, you might experience it most mornings, often with no apparent cause.

Eleven Strategies to Minimize Morning Anxiety

1. Plan your day the night before.

Focus on what you can control and choose things to give you a sense of accomplishment. Stick to small, concrete tasks you can start and finish, and avoid overloading yourself.

2. Create a calming morning routine.

Depending on how much time you have, you can choose from any of these options:

- Meditate for 10 to 20 minutes (or longer).

- Create a short list of things you’re grateful for.

- Spend 15 minutes journaling. Write down your worries and let them go for the day.

- Read something short and uplifting.

3. Avoid social media, news, and email if possible.

All of these things contribute to stress. Social media and news tend to exaggerate the negative and are predominantly fear-based. Email, especially concerning work, revs up your stress meter.

4. Drink a full glass of water first thing.

Even if you drink coffee in the morning, make an effort to drink water first. Since your brain is 70% water, staying hydrated can be calming and energizing and help balance your emotions.

5. Do four rounds of square breathing.

Connecting to your breath is a quick way to diminish anxiety. Inhale for four counts, hold for four counts, and exhale for four counts. Do that four times.

6. Exercise.

Exercise, especially aerobic exercise, increases serotonin, creates endorphins, and raises the stress threshold. It also relaxes muscle tension and regulates your breath.

If you can’t do aerobic exercise (walking works), try something calming like yoga. Even a small amount of exercise can help reduce anxiety and shift your mindset for the day.

7. Eat a nutritious breakfast.

Some people wake up with low blood sugar and need a pick-me-up immediately. A piece of raw fruit will do the trick. Avoid a big, heavy breakfast with lots of fat, empty carbs, and added sugars.

8. Challenge runaway thoughts.

If you lapse into worst-case scenarios, challenge your thoughts. What’s the evidence? What are you exaggerating?

Watch out for all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralizations, and fear-based predictions.

Focus on meeting the day with your best efforts, and remind yourself that even if something goes wrong or you make a mistake, you can handle it and make corrections where necessary.

9. Improve your sleep.

Try to go to bed at the same time every night and arise at the same time every morning. Aim for 7 to 8 hours.

Establish a nighttime wind-down routine that helps you relax before bed.

Avoid screens (especially blue light) a few hours before sleep. If that’s difficult for you, try substituting activities you enjoy, such as reading, stretching, yoga, taking a warm bath, or focusing on your breath.

For more suggestions, check out this article.

10. Abstain from alcohol or caffeine in the evenings.

Both can significantly impair your sleep and leave you stressed and irritable in the morning.

11. Try tart cherries.

You can eat tart cherries if you can find them or drink tart cherry juice. I take a tart cherry supplement every evening with dinner, and my sleep has improved dramatically, especially my ability to stay asleep.

Tart cherries contain a small amount of melatonin and, with regular consumption, have significantly increased overall melatonin levels in research studies. It’s worth a try!

Last Thoughts

If you have generalized anxiety, panic attacks, or OCD symptoms, you can use all of the strategies in this article, but they may not be enough. Consult a therapist. Counseling can help.

You can also read about Acceptance-Commitment Therapy, which can be very helpful.

That’s all for today!

Have a great week!

All my best,

Barbara

FOOTNOTES

Blain, T. (2023, Nov. 9). 12 tips for better sleep with anxiety. Very Well Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-sleep-with-anxiety-5224455

Howatson, G., Bell, P. G., Tallent, J., Middleton, B., McHugh, M. P., & Ellis, J. (2012, Dec.). Effect of tart cherry juice (Prunus cerasus) on melatonin levels and enhanced sleep quality. European Journal of Nutrition. 51(8):909-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22038497/

Kay, I. (2019, Oct. 21). Is your mood disorder a symptom of unstable blood sugar? University of Michigan, School of Public Health. https://sph.umich.edu/pursuit/2019posts/mood-blood-sugar-kujawski.html

Martin, S. & Abulhosn, R. (2023, Sept. 27). Alcohol & anxiety: Connections & risks. Choosing Therapy. https://www.choosingtherapy.com/alcohol-anxiety/

Stalder, T., Kirschbaum, C., Kudielka, B. M., Adam, E. A., Pruessner, J. C., Wüst, S., Dockray, S., Smyth, N., Evans, P., Hellhammer D. H., Miller, R., Wetherell, M. A., Lupien, S. J., & Clow, A. (2016). Assessment of the cortisol awakening response: Expert consensus guidelines. Psychoneuroendocrinology, (63), 414-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.010

Dr. Nerurkar is a Harvard-trained stress expert who decided to pursue the study of stress and resilience when she experienced anxiety and involuntary heart palpitations that kept her up at night. She was a med student at the time and overworked, as most medical students are, and couldn’t think her way out of it.

Dr. Nerurkar is a Harvard-trained stress expert who decided to pursue the study of stress and resilience when she experienced anxiety and involuntary heart palpitations that kept her up at night. She was a med student at the time and overworked, as most medical students are, and couldn’t think her way out of it. The premise of this book is that we all live with a narrator in our heads.

The premise of this book is that we all live with a narrator in our heads. One of the opening statements in the first chapter of this book is:

One of the opening statements in the first chapter of this book is: Crucial Conversations is a detailed, actionable manual for how to navigate critical conversations successfully. The authors define a “crucial conversation” as a discussion between two or more people where there are: (1) opposing opinions, (2) high stakes, and (3) strong emotions.

Crucial Conversations is a detailed, actionable manual for how to navigate critical conversations successfully. The authors define a “crucial conversation” as a discussion between two or more people where there are: (1) opposing opinions, (2) high stakes, and (3) strong emotions. The Comfort Book is one of my all-time favorite books. It’s not a book to sit down and read cover to cover, although you could. It’s meant to be read slowly – one entry at a time.

The Comfort Book is one of my all-time favorite books. It’s not a book to sit down and read cover to cover, although you could. It’s meant to be read slowly – one entry at a time.