Blog Short #262: Feeling Burned Out by Hustle Culture? Time to Leave It Behind and Do This Instead

Photo by Jacob Wackerhausen

I’ve been writing my blog articles for five years now, and looking back at them, I’m noticing a pattern, which is: Choose a problem and offer strategies to resolve it.

That’s not a bad approach, and it’s the one recommended by writing mentors. Based on readership and feedback, it’s also helpful.

But sometimes it’s a good idea to focus on what you already have. In other words, assets instead of deficits. Today, I’ll show you how to take advantage of that and reduce burnout.

The Deficit Trap

Ask yourself this question:

“How am I doing right now in terms of my goals, life trajectory, and overall self-development?”

Take some time to answer. Jot it down.

How did you do? What’s the ratio of negative comments to positive ones? How many items did you list that refer to deficits, and how many to assets?

In other words, what was your primary focus: What you’ve done well, or what you’re lacking and not doing well?

Our natural go-to is usually negative. We look for what needs improvement. Not a bad thing because ignoring deficits can backfire. Sometimes significantly!

At the same time, it’s easy to get caught in the “deficit trap,” which always spotlights what’s wrong. And in doing that, ignore your assets: improvements, achievements, skills, and personal strengths.

If our negativity bias isn’t enough to tip the scale, our current hustle culture will do it for us.

Hustle Culture

The “hustle culture” broadcasts daily that you need to work harder, longer, take on more and more, and do it all well.

Social media is the handmaiden of the hustle culture because it screams at you that you aren’t as successful as someone else, that you aren’t getting the same great results others are getting, and that you need to do more.

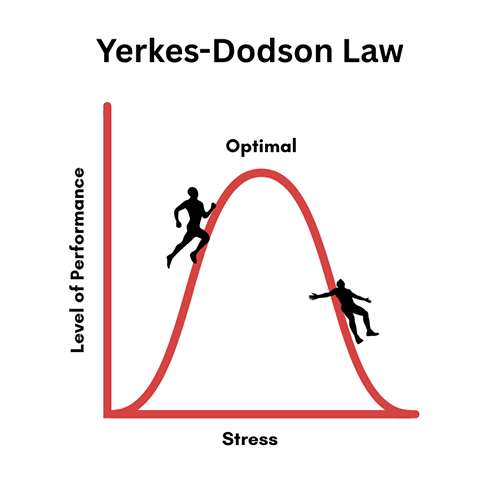

It’s a culture of extremism that leads to stress and burnout.

And it reminds you daily of your deficits, with small reprieves here and there when you achieve a goal. However, when you do that, new demands flood in, leaving you no time before you’re back on the treadmill, running at breakneck speed.

Maybe your life isn’t that way, and if not, it’s a good thing. But no one in our current culture is immune to the pressure to perform.

So what’s the answer?

Shift your mindset from the deficit trap to an asset-driven approach based on your values and strengths. Here’s how.

Identify Your Personal Assets

Personal assets are what you already have that will help you choose what you do, how you do it, and what it means to you.

Even if your life circumstances – for example, your job – are not optimal for you, you can use your assets to improve not only how you do it, but how you feel about it and what it means for you.

There are four types of assets to consider. Here they are.

1. Skills

What do you naturally do well or have learned through effort and experience?

These are concrete skills you acquired, such as leadership, management, bookkeeping, plumbing, or computer coding. List them all. You likely have more skills than you realize, and seeing them will broaden your view of what you’re good at and what interests you. That last phrase is important and needs repeating: what you’re good at and what interests you.

2. Traits

This category includes personal traits such as persistence, working well with others, empathy, kindness, insightfulness, curiosity, humor, creativity, organization, conscientiousness, honesty, and any others that apply to you.

Be careful you don’t shift to deficits while doing this exercise by adding a “but” to anything you list. We’re focusing on positives right now.

3. Values

Values are assets because they provide meaning and guide your choices of activity and behavior. What is most important to you?

There are four parts to this question:

- What behavior is acceptable to you?

- What provides meaning and initiates motivation for you?

- Who do you aspire to be?

- What values are non-negotiable?

This exercise could be a full project in itself, but for now, jot down what comes to mind easily and let it rest for a few days. You can refine it later. What’s important is recognizing that your values are personal assets that guide your actions.

4. Experiences

What have you accomplished?

List challenges you’ve navigated, insights you’ve acquired, and any areas of resilience you’ve achieved. This is a list all of us should make more often to remind ourselves of what we’ve succeeded at and learned.

It’s easy to forget about these achievements when you focus on what you lack.

How to Use Your Assets

Now that you’ve completed the exercise, do you have a different picture of yourself and how you’re doing? Hopefully so.

Let’s capitalize on that. Using all of this information, you can reassess where you are and decide if your current life is aligned with what you’re good at, what you value, and what you aspire to be.

Not someone else’s version, and not in comparison to anyone else. You are your own measuring stick.

Given your current life circumstances, how can you apply this information right now?

If you have a job that you don’t love, is there some aspect of it you can use to accomplish something that will give you satisfaction and reflect your assets? Maybe a particular skill you’re building, or an opportunity to use your personal traits to provide value.

In the meantime, if you don’t like where you are, you can start thinking about what you would like to do instead and begin exploring possibilities.

If you’re caught up in hustle culture and have ignored your relationships, you might cut back on work and spend more time with family and friends.

Hustle culture is detrimental to your health, both mental and physical.

We’re not meant to “do it all,” and trying to push ourselves to do that doesn’t bring true happiness.

It usually pulls us away from our most important values, not to mention creating burnout, sometimes permanently.

Do One Thing Well

One way to work toward defeating the deficit trap is to focus on one thing with an improvement mindset.

You can attach an end goal or result, but the real intrinsic value is in the process of doing it and feeling the rewards of small steps forward.

It can be something related to work or something you would just enjoy. Maybe improving a work-related or future-work skill could be a good choice. Or something like learning a language, or cataloging all your family photos and creating photo albums.

It could be something more intimate, like showing kindness to your spouse, kids, or colleagues at work, twice a day, every day, for a month.

Choose something that uses your natural and acquired assets.

By noting those as you’re working on something, you can approach your activity with more motivation because you’re building, not deleting.

Make sure whatever you choose is aligned with your values. That will provide more staying power and increase your satisfaction as you proceed.

The odd thing about goals is that they give us an anchor to work toward, but once we reach them, our satisfaction wanes quickly, and we’re on to the next goal.

The real pleasure is in the process of becoming. And when you know that, you don’t mind mistakes and setbacks because they’re part of your growth journey.

A Recommendation

This article was prompted by a podcast featuring Brad Stulberg, whose new book is The Way of Excellence. I’ve purchased it and will let you know how it is.

In the meantime, focus on your assets and make use of them. You’ll feel more inspired.

That’s all for today.

Have a great two weeks!

All my best,

Barbara