Blog Short #263: Why Are Some People Always In Crisis?

Photo by Rachel Coyne on Unsplash

Why do some people seem to thrive during a crisis and not so much otherwise? They, in fact, seek out crises and sometimes initiate them.

For example, being late for an important appointment and then reacting dramatically to perceived consequences. Or overspending without minding their bank account balance, and freaking out when they can’t pay the rent.

There are many reasons.

Let’s review them today, and I’ll give you some guidelines for how to best respond.

We’ll begin with some common reasons why someone might be in crisis mode much of the time.

Chronic Emptiness

Feeling flat and empty is uncomfortable and can lead someone to seek ways to generate energy and interest.

This feeling is felt both emotionally and physically as a lack of drive, along with numbness and sometimes depression.

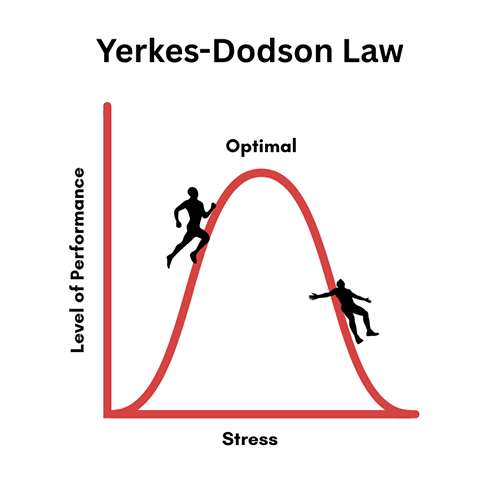

By seeking a crisis or creating one, you trigger the release of adrenaline. It’s energizing. You become immersed in something outside yourself. You feel alive rather than numb and flat.

Because you’re unable to generate this feeling internally, you need an outside source to do it for you.

Someone who chronically feels empty gravitates toward crises and chaos to stave off that emptiness.

Need For Attention

When someone is in crisis, all eyes turn to them.

Some people do this by being loud and dramatic, which works right away.

Yet other times, it comes from a shy, quiet person who isn’t loud but who draws attention to themselves with endless complaining about things happening to them.

Nothing ever goes right for this person.

The dramatic person immediately captures the attention of those around them and requires soothing, empathy, and, often, active assistance.

However, the quiet person displays a persistent helplessness that also draws people to them, prompting offers of help.

Either way, the need for attention is temporarily satisfied until the next incident.

It’s Familiar

I once knew a family with seven children that lived in constant chaos. Literally, their house was cluttered and in total disarray. There wasn’t a room you could walk into that wasn’t messy and disorienting.

There were few boundaries between the kids, their stuff, and their activities. They were wild.

The mom was oblivious, depressed, and dramatic, and she encouraged the chaos.

The father was a very successful physician whose life revolved around his career. When he was home, he was emotionally abusive and highly critical.

This family was very well-off financially, but they lived in a chronic state of crisis.

Growing up in a family where crisis and chaos are the norm can make them seem “normal.”

As an adult, a person with this history may seek out the same environment by either creating it or finding it. It’s embedded in their personality. It’s their emotional home.

Personality Disorders

There are three personality disorders known as Cluster B disorders that involve the frequent use of crises. These are Borderline, Narcissistic, and Antisocial. They’re grouped together because they’re notable for their use of drama, emotional reactivity, and erratic behavior.

People who have these disorders are more prone to creating and needing crises to deal with their particular psychological issues.

Borderline Personality

Borderlines are highly attention-seeking, fear abandonment, need intimacy but can’t sustain it, and are often chaotic. They use crises to get the attention they seek and avoid abandonment.

Conversely, they use it to create distance in a relationship when they feel too close.

There’s a constant push-pull, often facilitated by drama and anger. You never know where you stand. It’s chaotic.

Narcissistic Personality

Narcissists, on the other hand, have some similar issues, but they’re smoother in their manifestation. They require constant admiration and need to one-up to feel superior.

Narcissists can idealize you initially and drop you in an instant later. They’re unable to feel true empathy. They use crises to distance themselves. They may also use them to create circumstances that make them appear to be the hero.

Antisocial Personality

Antisocial Personalities are rule-benders and, at the more extreme end, criminals.

They’re master manipulators to get what they want, and will use a crisis to distract and gain the emotional upper hand to maintain control over you until they have what they want.

Antisocial personalities lack a conscience. They can be very charming and smooth, easily deceiving others for their own gain. They’re master scammers.

What’s most dangerous is the combination of narcissistic and antisocial traits used together. The extreme is a Psychopath who consistently uses crises to distract from his maladaptive and criminal behavior.

Personality disorders exist on a scale, which means that someone can meet the criteria for the diagnosis, but operate at the high end of the spectrum. It’s not a one-size-fits-all when it comes to diagnosing.

More important is recognizing each person as an individual and identifying where problems exist and how to address them.

For example, a high-functioning borderline can be a good parent, stay in a relationship, and use insight and therapy to overcome their issues.

For our purposes here, if you live with or deal regularly with someone who seems to be in a constant state of crisis, or who consistently creates them, a personality disorder could be part of the problem. But not always. Each case is individual.

What to Do

When dealing with someone who appears to be in perpetual crisis or regularly creates chaos, there are strategies that can help lower the emotional temperature.

1. React Calmly

When someone overacts, it’s best for you to underreact initially. In other words, be quiet. Speak calmly. Match the other person’s intensity with a lack of intensity and reactivity.

Dramatic people have a need to sweep everyone up into their whirlwind. If you don’t comply immediately, they may raise the bar by upping the emotional noise or by provoking you to join in.

If you’re caught off guard, you might be pulled in before you have a chance to create some emotional space and set a boundary.

In cases where the situation is obviously not a crisis, you can step out of the conversation or avoid it until the person has calmed down and can approach it more logically.

Some people are naturally more sensitive and become reactive quickly. However, if you don’t respond immediately and give them some time to calm down, the crisis often subsides. They just needed some time.

Part of dealing with these situations is discerning when someone needs immediate assistance or when it’s best to give them some space before helping.

2. Investigate

If you suspect the crisis is a cover for some other feeling or problem, investigate. Instead of reacting to the words you’re hearing, ask about the underlying emotions.

Ask a simple question like, “What about this situation is upsetting you the most right now?”

Doing that initiates a more cognitive approach to what’s happening. The other person has to use their thinking brain and analyze how they’re feeling rather than just acting it out.

As they provide answers, you can keep asking questions until the emotional temperature has dropped considerably and you’re getting to the bottom of what’s going on.

This approach is particularly effective when someone is trying to cover up a vulnerability.

For example, they may feel abandoned, insecure, hurt, or insignificant. Moving the conversation toward a more analytical exchange while remaining empathetic helps uncover what’s going on and correct or dispel distorted perceptions.

3. Opt Out

If you know the crisis is being used to manipulate in some way, you don’t need to participate at all. You can opt out without any interaction.

Often, the best response in cases like this is no response at all.

You make your excuses and leave, or simply don’t respond and wait for the other person to continue.

When you meet drama with silence, the other person will move on to someone else. Or, they’ll calm down. They may try to provoke you, but if you continue not to respond, they’ll give up.

One way you know that it’s not worth responding is when they resort to personally attacking you.

Once someone makes that shift, you know they’re attempting to manipulate you.

Set a boundary in these cases. Let them know you won’t continue, or simply walk away. People who use drama to manipulate can only be successful if you play along.

Two Ways People Use Words

One of the most helpful things I learned about communication is that people use words in two ways.

The first is a direct approach. You say what you mean in a way that’s clear, easy to understand, and matches your intent. In other words, the purpose of the communication is to have a genuine conversation in which both people seek to understand each other. There are no hidden agendas.

The second approach is indirect. Words are used to evoke emotions in the other person. The actual words used may not match the intended message. There are ulterior motives. You sense that you’re not hearing the whole message. It’s confusing.

The second type of communication is commonly used by people who need drama and who don’t reveal their true feelings up front. They use crisis to avoid underlying issues, or, at worst, use words to manipulate by toying with emotions.

When in doubt, ask yourself whether the person speaking is trying to make you feel something without saying it directly, or whether they actually want to communicate and are direct about it.

Someone may not do any of this deliberately if they’re upset, but more often, people know on some level when they’re trying to evoke emotions.

For instance, if someone’s hurt but doesn’t want to say it, they’ll say something else to make you feel guilty without being direct about it.

If what you hear is confusing, pause and be quiet for a moment, which stops the dramatic flow, and then calmly ask, “What’s really bothering you?” or “What is it you really want to say?”

If you’re dealing with someone close to you, using this strategy will help them learn to approach their emotions more directly and verbalize them rather than act them out by creating crises and drama.

You get the benefit of not having to deal with those episodes, and they get the benefit of learning how to handle their emotions more appropriately. It’s a win-win.

Last Note

If you are someone who gravitates toward crises, do some exploring.

How does it serve you and how not? What other issues or feelings might you be covering or avoiding that you could work on more directly?

We all have some drama in us, but you don’t want it to be your primary mode of dealing with things. Use it sparingly.

A caveat: Keep in mind that people have real crises that require empathy, understanding, and help. What we’ve been talking about today is different. It’s about chronic crises, often manufactured to address other underlying issues.

That’s all for today.

Have a great two weeks!

All my best,

Barbara